Ted Hubbard is a long-time rider who discovered flat tracking later in life, but is so passionate about it that he was awarded a placard by Eddie Mulder that reads, “To a man who loves dirt track: Big Ted.” He races for Linda’s Checkbook Racing, and has competed on Mule trackers and Eddie Mulder Specials in both flat tracking and the revered Pikes Peak International Hillclimb. But Hubbard is a breath of fresh air in a typically cutthroat community: he just does it ‘cause he loves it.

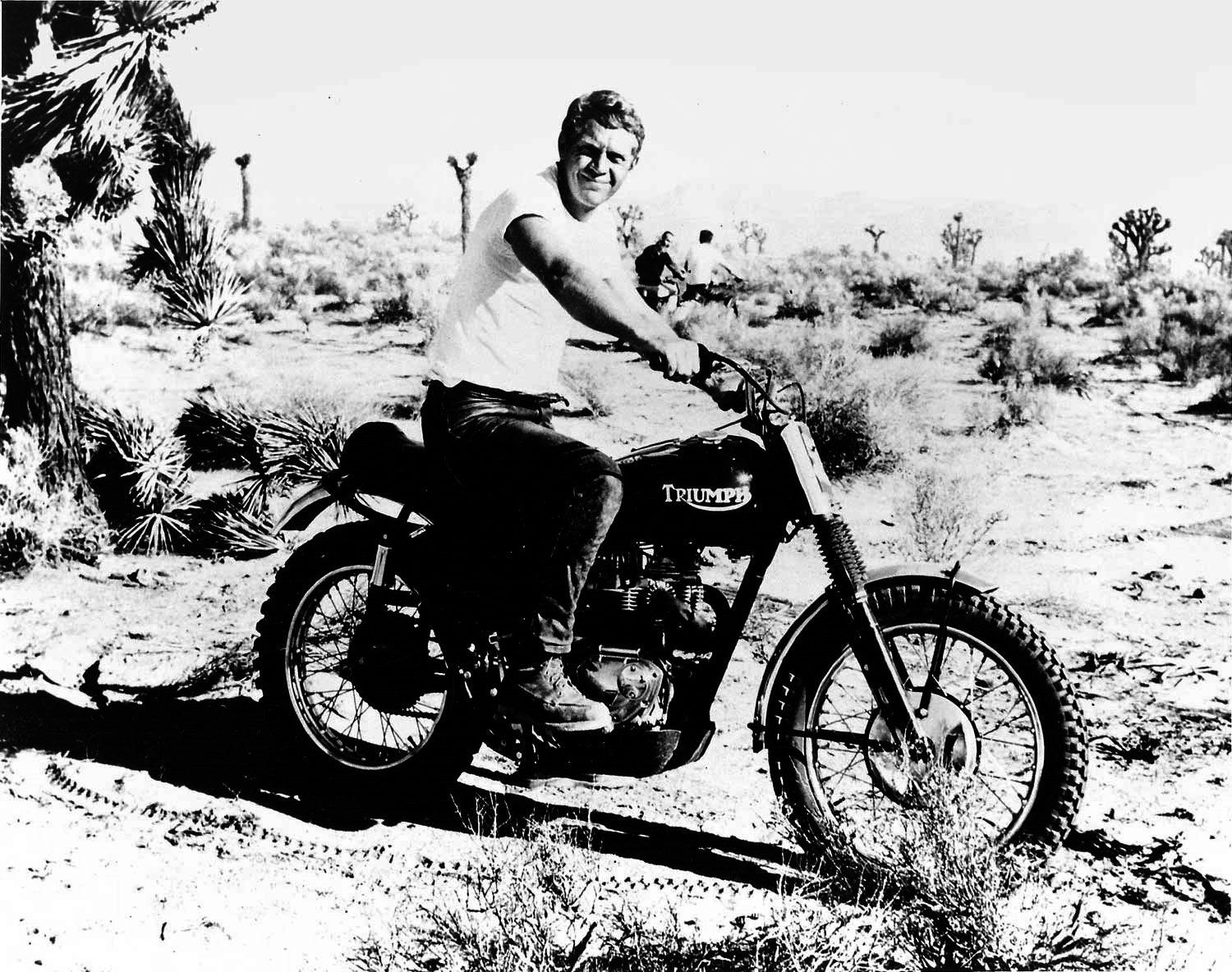

Hubbard’s first two-wheeled experience came in high school when he bought a tote gote in the 60s. His father threw a fit when he brought it home, and Hubbard’s first thought was, “This is going to be fun.” A tote gote, if you didn’t know, has a lawnmower engine and two tiny tractor-style wheels; and they’re considered farm or ranch tools. Later, in 1969, Hubbard found himself in the army and stationed in Germany, where he purchased a Triumph Bonneville.

When he came back to the States, the bike needed too much work to register it in California, so he sold it and started buying cruisers.

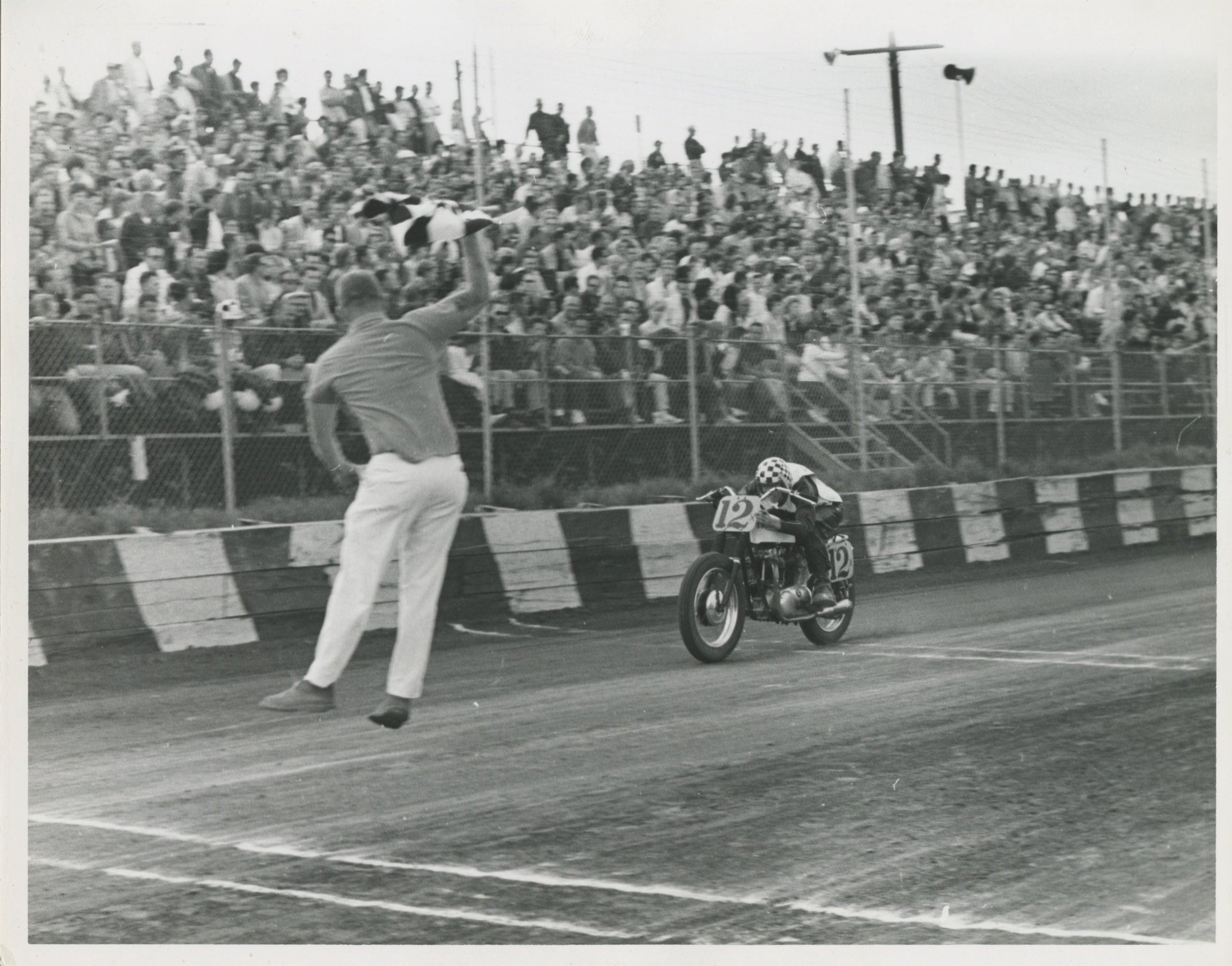

In 2001, Hubbard and his wife Linda, both Southern Californians, decided to attend a race at the local-but-iconic Costa Mesa Speedway. Before the races, there was a hooligan parade where anyone could ride a lap around the track, and Hubbard decided he wanted to do it. His wife told him he was nuts for wanting to wreck all the chrome by getting the bike sandblasted for the sake of just doing a glory lap, and Hubbard said he knew that, but he just wanted to do it because it sounded like fun.

It was so fun, and the races were so exciting, that Hubbard decided he wanted to get into dirt tracking. Hubbard is well over six feet tall, and at the time weighed about 400 pounds. Linda told him again that he was crazy, and he said he knew, and she demanded the checkbook. He got in contact with legendary custom motorcycle builder and godfather of the street tracker Richard Pollock of Mule Motorcycles, and asked Pollock to build him a flat tracker.

Pollock tried to sell him on a Yamaha 650, but Hubbard wanted a Harley. They ended up buying a 1200 cc Buell at an insurance sale, and set to work building a mono-shock flat tracker for him. In the meanwhile, Hubbard went down to NJK Leathers to have a custom flat track suit made. When discussing the graphics he wanted on the suit, he was asked who his main sponsor was. Hubbard laughed and answered, “Well, Linda’s checkbook is paying for all this, so Linda’s checkbook is my main sponsor.” Thus was born Linda’s Checkbook Racing Team.

Once Hubbard got the Mule Buell back, he immediately began flat tracking. Which is how he met Eddie Mulder.

In 2004, Hubbard competed in a race at the Victorville Speedway where Mulder was a spectator. After the race, Mulder went and found Hubbard and told him he was going to get himself killed on that bike — even though it was unmarked, he recognized it as a Mule bike — and that he should come to Mulder’s school to really learn how to race.

So Hubbard did, and so began their friendship.

At Mulder’s school, which Hubbard ended up attending twice, Hubbard learned that when Mulder yells at you, “he’s telling you he likes ya. That’s Mr. Mulder.” Hubbard also learned that “winning is a habit: champions train, and losers complain.”

During the rider’s meeting in the morning, Hubbard had his first experience of Mulder: a competitor raised his hand and asked Mulder a less-than-impressive question, to which Mulder responded, “That’s a stupid question. How much did you pay to register? Go get your money back and however much you spent on gas and go home.”

But such a gruff answer from Mulder would prove misleading of Mulder’s true character, as Hubbard would learn over the years.

In contrast to Mulder’s extreme competitiveness, Hubbard brings a sense of humor to racing. Hubbard does it because he loves it, and wants to have fun. “All the pictures of me racing are in pretty good focus. I don’t really go fast enough to make me look blurry.” One of his favorite races was when he and Bob Harris (who was Elvis Presley’s stunt double, and 80 years old at the time) were fighting for last in a vintage class race at the Willow Springs International Raceway. The two fought so hard and were so much fun to watch that they received a standing ovation when the race finished.

In the beginning, he crashed with a degree of frequency, and even brings a sense of humor to that: he has a patch with his primary care physician’s name on the left sleeve of his track suit.

Hubbard recalls his worst crash with a laugh. “I woke up in a CT scan machine, and thought I must have been in a wreck. So I looked down and sure enough, there was dirt in my underwear. I asked the technician if my wife was there, and when he said yes I asked if she was mad. He said she wasn’t, so I asked if he could bring her in. When she came in I asked when I crashed, and she told me it was during turn one.”

Linda tending to Ted’s finger between heats, which had 21 stitches in it after a close call with a table saw.

Hubbard and Mulder grew close, and they would get together with master engine builder Karl Krohn and work on bikes and talk shop on the weekends when they weren’t racing.

In 2006, Hubbard was diagnosed with squamous cell cancer, and underwent multiple surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. He dropped from 400 pounds down to 200, and was unable to speak or swallow for a long time, and had to have Linda translate for him. Mulder, however, was one of the few people who called or visited every week to check on how he was doing. Once Hubbard started getting stronger, Mulder invited him up to his house because he said he had a surprise for Hubbard. Mulder brought him over to the garage, where he was presented with an Eddie Mulder Special built just for Hubbard: a Yamaha TT 540, tuned and built by only the best: Mulder designed it, and Krohn built the engine. (It’s also the only Eddie Mulder Special in existence that wasn’t built from a Triumph.) “Ted,” Mulder told him, “We’re going to Pikes Peak.”

They then registered to compete in one of the most infamous and challenging races in the world: Pikes Peak International Hillclimb. Hubbard forged a doctor’s note so he could play hooky from chemo and race. At PPIHC’s tech inspection, Mulder distracted the officials and pushed both of their bikes through because he knew Hubbard’s bike wouldn’t pass inspection, besides all the sideways looks they were giving the feeding tube Hubbard had in his neck.

“Pikes Peak’s 156 turns over 12.4 miles will catch your attention in a heartbeat,” Hubbard recalls. “I never rode so fast in my whole life as I did in that race. I was focused like you could not believe. I was in the zone. And I remember I was riding full throttle down a straight called Halfway Picnic Ground when all of a sudden I got a tap on the shoulder and it scared the bejeesus out of me — it was Eddie giving me the thumbs up, checking if I was feeling okay. I gave him the thumbs up back, and he waved goodbye and ripped off into the distance. When I got to the top, I pulled off my helmet thinking, ‘That was a rush!’ when Eddie walked over and asked where I’d been. He told me I was late!”

Years later, at a major flat track race marshaled by Mulder in which Hubbard competed, Mulder presented Hubbard with a placard that said, “To a man who loves dirt track: Big Ted.” The placard is now displayed in a place of honor in Hubbard’s garage.

“I’ve had the motorcycle disease for a long time. I don’t think it’s curable. I’m going to keep on racing. Thank you, Eddie Mulder.”

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.